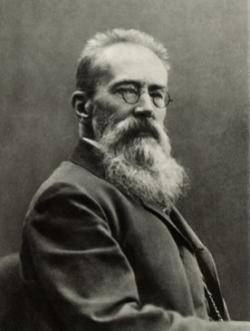

Rimsky-korsakov Russian Easter Overture Program Notes

| Scheherazade | |

|---|---|

| Symphonic suite by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov | |

| Catalogue | Op. 35 |

| Based on | One Thousand and One Nights |

| Composed | 1888 |

| Performed | 1888 |

| Movements | Four |

| Scoring | Orchestra |

Scheherazade, also commonly Sheherazade (Russian: Шехераза́да, tr.Shekherazáda, IPA: [ʂɨxʲɪrɐˈzadə]), Op. 35, is a symphonic suite composed by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1888 and based on One Thousand and One Nights (also known as The Arabian Nights).[1]

This orchestral work combines two features typical of Russian music and of Rimsky-Korsakov in particular: dazzling, colorful orchestration and an interest inthe East, which figured greatly in the history of Imperial Russia, as well as orientalism in general. The name 'Scheherazade' refers to the main character Shahrazad of the One Thousand and One Nights. It is considered Rimsky-Korsakov's most popular work.[2]

Program Notes. Gioachino Rossini: Tancredi Overture Bernd Alois Zimmermann. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov 1844–1908. Russian Easter Festival Overture, Op. Work composed: 1887–88. An Easter overture based on music from the obikhod, a collection of chants used in Russian Orthodox liturgy. Families of instruments (winds, strings, brasses. Note: Citations are based on reference standards. However, formatting rules can vary widely between applications and fields of interest or study. The specific requirements or preferences of your reviewing publisher, classroom teacher, institution or organization should be applied. NIKOLAI RIMSKY-KORSAKOV: Russian Easter Overture. Tonight’s all-Russian concert opens with a concert overture dedicated to two giants of Russian music, Modeste Mussorgsky and Alexander Borodin. “The Great Russian Easter Overture” stands with Scheherazade and Capriccio Espagnol as the last of three orchestral showpieces Rimsky-Korsakov.

- 2Music

- 3Adaptations

Background[edit]

During the winter of 1887, as he worked to complete Alexander Borodin's unfinished opera Prince Igor, Rimsky-Korsakov decided to compose an orchestral piece based on pictures from One Thousand and One Nights as well as separate and unconnected episodes.[3] After formulating musical sketches of his proposed work, he moved with his family to the Glinki-Mavriny dacha, in Nyezhgovitsy along the Cherementets Lake (near present-day Luga, in Leningrad Oblast). The dacha where he stayed was destroyed by the Germans during World War II.

During the summer, he finished Scheherazade and the Russian Easter Festival Overture. Notes in his autograph orchestral score show that the former was completed between June 4 and August 7, 1888.[4]Scheherazade consisted of a symphonic suite of four related movements that form a unified theme. It was written to produce a sensation of fantasy narratives from the Orient.[5]

Initially, Rimsky-Korsakov intended to name the respective movements in Scheherazade 'Prelude, Ballade, Adagio and Finale'.[6] However, after weighing the opinions of Anatoly Lyadov and others, as well as his own aversion to a too-definitive program, he settled upon thematic headings, based upon the tales from The Arabian Nights.[3]

The composer deliberately made the titles vague so that they are not associated with specific tales or voyages of Sinbad. However, in the epigraph to the finale, he does make reference to the adventure of Prince Ajib.[7] In a later edition, Rimsky-Korsakov did away with titles altogether, desiring instead that the listener should hear his work only as an Oriental-themed symphonic music that evokes a sense of the fairy-tale adventure[4], stating:

All I desired was that the hearer, if he liked my piece as symphonic music, should carry away the impression that it is beyond a doubt an Oriental narrative of some numerous and varied fairy-tale wonders and not merely four pieces played one after the other and composed on the basis of themes common to all the four movements.

He went on to say that he kept the name Scheherazade because it brought to everyone’s mind the fairy-tale wonders of Arabian Nights and the East in general.[3]

Music[edit]

Rimsky-Korsakov. Scheherazade, Symphonic Suite, Op. 35 Performed by the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra conducted by Pierre Monteux, with violin solo by Naoum Blinder | |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Overview[edit]

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote a brief introduction that he intended for use with the score as well as the program for the premiere:

The Sultan Schariar, convinced that all women are false and faithless, vowed to put to death each of his wives after the first nuptial night. But the Sultana Scheherazade saved her life by entertaining her lord with fascinating tales, told seriatim, for a thousand and one nights. The Sultan, consumed with curiosity, postponed from day to day the execution of his wife, and finally repudiated his bloody vow entirely.[8]

The grim bass motif that opens the first movement represents the domineering Sultan.[4]

This theme emphasizes four notes of a descending whole tone scale: E-D-C-B♭[9] (each note is a down beat, i.e. first note in each measure, with A♯ for B♭). After a few chords in the woodwinds, reminiscent of the opening of Mendelssohn'sA Midsummer Night's Dream overture,[7] the audience hears the leitmotif that represents the character of the storyteller herself, Scheherazade. This theme is a tender, sensuous winding melody for violinsolo,[10] accompanied by harp.[8]

Rimsky-Korsakov stated:

[t]he unison phrase, as though depicting Scheherazade’s stern spouse, at the beginning of the suite appears as a datum, in the Kalendar’s Narrative, where there cannot, however, be any mention of Sultan Shakhriar. In this manner, developing quite freely the musical data taken as a basis of composition, I had to view the creation of an orchestral suite in four movements, closely knit by the community of its themes and motives, yet presenting, as it were, a kaleidoscope of fairy-tale images and designs of Oriental character.[3]

Rimsky Korsakov List Of Works

Rimsky-Korsakov had a tendency to juxtapose keys a major third apart, which can be seen in the strong relationship between E and C major in the first movement. This, along with his distinctive orchestration of melodies which are easily comprehensible, assembled rhythms, and talent for soloistic writing, allowed for such a piece as Scheherazade to be written.[11]

The movements are unified by the short introductions in the first, second and fourth movements, as well as an intermezzo in the third. The last is a violin solo representing Scheherazade, and a similar artistic theme is represented in the conclusion of the fourth movement.[4] Writers have suggested that Rimsky-Korsakov's earlier career as a naval officer may have been responsible for beginning and ending the suite with themes of the sea.[8] The peaceful coda at the end of the final movement is representative of Scheherazade finally winning over the heart of the Sultan, allowing her to at last gain a peaceful night's sleep.[12]

The music premiered in Saint Petersburg on October 28, 1888 conducted by Rimsky-Korsakov.[13]

The reasons for its popularity are clear enough; it is a score replete with beguiling orchestral colors, fresh and piquant melodies, a mild oriental flavor, a rhythmic vitality largely absent from many major orchestral works of the later 19th century, and a directness of expression unhampered by quasi-symphonic complexities of texture and structure.[11]

Instrumentation[edit]

The work is scored for an orchestra consisting of:[13]

|

|

Movements[edit]

The work consists of four movements:

| I. | The Sea and Sinbad's Ship Largo e maestoso – Lento – Allegro non troppo – Tranquillo (E minor – E major) This movement is made up of various melodies and contains a general A B C A1 B C1 form. Although each section is highly distinctive, aspects of melodic figures carry through and unite them into a movement. Although similar in form to the classical symphony, the movement is more similar to the variety of motives used in one of Rimsky-Korsakov's previous works, Antar. Antar, however, used genuine Arabic melodies as opposed to Rimsky-Korsakov’s own ideas of an oriental flavor.[11] |

| II. | The Kalandar Prince Lento – Andantino – Allegro molto – Vivace scherzando – Moderato assai – Allegro molto ed animato (B minor) This movement follows a type of ternarytheme and variation and is described as a fantastic narrative.[by whom?] The variations only change by virtue of the accompaniment, highlighting the piece's 'Rimsky-ness' in the sense of simple musical lines allowing for greater appreciation of the orchestral clarity and brightness. Inside the general melodic line, a fast section highlights changes of tonality and structure.[11] |

| III. | The Young Prince and The Young Princess Andantino quasi allegretto – Pochissimo più mosso – Come prima – Pochissimo più animato (G major) This movement is also ternary and is considered the simplest movement in form and melodic content. The inner section is said to be based on the theme from Tamara, while the outer sections have song-like melodic content. The outer themes are related to the inner by tempo and common motif, and the whole movement is finished by a quick coda return to the inner motif, balancing it out nicely.[11] |

| IV. | Festival at Baghdad. The Sea. The Ship Breaks against a Cliff Surmounted by a Bronze Horseman Allegro molto – Lento – Vivo – Allegro non troppo e maestoso – Tempo come I (E minor – E major) This movement ties in aspects of all the preceding movements as well as adding some new ideas, including an introduction of both the beginning of the movement and the Vivace section based on Sultan Shakhriar’s theme, a repeat of the main Scheherazade violin theme,[11] and a reiteration of the fanfare motif to portray the ship wreck.[3] Coherence is maintained by the ordered repetition of melodies, and continues the impression of a symphonic suite, rather than separate movements. A final conflicting relationship of the subdominant minor Schahriar theme to the tonic major cadence of the Scheherazade theme resolves in a fantastic, lyrical, and finally peaceful conclusion.[11] |

Adaptations[edit]

Ballet[edit]

A ballet adaptation of Scheherazade premiered on June 4, 1910, at the Opéra Garnier in Paris by the Ballets Russes. The choreography for the ballet was by Michel Fokine and the libretto was from Fokine and Léon Bakst.

This ballet provoked exoticism by showing a masculine Golden Slave, danced by Vaslav Nijinsky, seducing Zobeide, danced by Ida Rubinstein, who is one of the many wives of the Shah. Nijinsky was painted gold and is said[citation needed] to have represented a phallus and eroticism is highly present in the orgiastic scenes played out in the background. Controversially, this was one of the first instances of a stage full of people simulating sexual activity. Nijinsky was short and androgynous but his dancing was powerful and theatrical.

When the Shah returns and finds his wife in the Golden Slave's embrace, he sentences to death all of his cheating wives and their respective lovers. It is rumored[citation needed] that in this death scene, Nijinsky spun on his head. The ballet is not centered around codified classical ballet technique but rather around sensuous movement in the upper body and the arms. Exotic gestures are used as well as erotic back bends that expose the ribs and highlight the chest. Theatrics and mime play a huge role in the story telling.

Scheherazade came after Petipa's Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty, which were ballets strongly focused on classical ballet and technique. Fokine embraced the idea of diminished technique and further explored this after Scheherazade when he created Petrouchka in 1912. He went on to inspire other choreographers to throw away technique and embrace authenticity in movement.

Bakst, who designed the sets and costumes for Scheherazade, had a big influence on interior design and fashion of that time by using unorthodox color schemes and exotic costuming for the ballet.

The widow of Rimsky-Korsakov protested what she saw as the disarrangement of her husband's music in this choreographic drama.[14]

Others[edit]

Rimsky Korsakov Operas

Sergei Prokofiev wrote a Fantasia on Scheherazade for piano (1926), which he recorded on piano roll.

Fritz Kreisler arranged the second movement (The Story of the Kalendar Prince) and the third movement (The Young Prince and the Princess) for violin and piano, giving the arrangements the names 'Danse Orientale' and 'Chanson Arabe', respectively.

In 1959, bandleader Skip Martin adapted from Scheherazade the jazz album Scheherajazz (Sommerset-Records),[15] in which the lead actress, Yvonne De Carlo, was also the principal dancer. The plot of this film is a heavily fictionalized story, based on the composer's early career in the navy. He was played by Jean-Pierre Aumont.[16]

Scheherazade is a popular music choice for competitive figure skating. Various cuts, mainly from the first movement, were widely used by skaters, including:

- Midori Ito during the 1989–1990 season

- Michelle Kwan during the 2001–2002 season

- Yuna Kim during the 2008–2009 season to her world championship gold

- Mao Asada during the 2011–2012 season

- Carolina Kostner during the 2013–2014 season

- Wakaba Higuchi during the 2016–2017 season

Notably, American figure skater Evan Lysacek used Scheherazade in his free skate and won the gold medal at 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver.[17] It was also used by American ice dancersCharlie White and Meryl Davis in their free dance, with which they won the gold medal at 2014 Winter Olympics.[18]

Recordings[edit]

- Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Leopold Stokowski (Victor Recording, 1927; re-released Biddulph, 1993).

- Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Leopold Stokowski (Victor Recording, 1934; re-released Cala, 1997).

- San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Pierre Monteux (Victor, recorded March 1942).

- Paris Conservatoire Orchestra, conducted by Ernest Ansermet (Decca, recorded May 1948).

- London Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Leopold Stokowski (1951; re-released Testament, 2003).

- Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Zdeněk Chalabala (Supraphon LP. 1955; re-released Supraphon CD 2012).

- Morton Gould and his Orchestra, (violin – Max Pollikoff) (Red Seal, 1956).

- London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Pierre Monteux (Decca, recorded June 1957).

- Orchestra of the Vienna State Opera, conducted by Mario Rossi, Vanguard Recording Society, 1957 [1].

- Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham (EMI, 1957).

- Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, conducted by Ernest Ansermet (Decca, 1958).

- Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Antal Doráti (Mercury Living Presence, 1959).

- New York Philharmonic, conducted by Leonard Bernstein (Columbia Masterworks, 1959; later released on Sony Masterworks).[when?]

- Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Paul Kletzki (violin – Hugh Bean) (EMI, 1960; later released on Classics for Pleasure).[when?]

- Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Fritz Reiner (RCA Victor Red Seal, 1960).

- Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Leopold Stokowski (1962 (live recording), Guild GHCD 2403, distr. by Albany).[when?]

- Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Eugene Ormandy (Columbia Masterworks, 1962; later released on Sony Masterworks).[when?]

- London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leopold Stokowski (violin – Erich Gruenberg) (1964. Re-released on Cala, 2003).

- Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Constantin Silvestri (violin – Gerald Jarvis) (EMI 1967; re-released Disky CD 2001).

- Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Herbert von Karajan (Deutsche Grammophon, 1967).

- USSR Symphony Orchestra conducted by Yevgeny Svetlanov (Columbia Masterworks Records, 1969; Melodiya LP, 1980; re-released Melodiya CD, 1996).

- Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Leopold Stokowski (RCA Red Seal LP and CD, 1975).

- Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Konstantin Ivanov (violin – Yoko Sato) (live broadcast recording from Radio Petersburg, 1978).[citation needed]

- Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, conducted by Kirill Kondrashin (Philips, 1979).

- London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Loris Tjeknavorian (recorded 1979, released on LP Chalfont Records 1980; released on CD Varese Sarabande 1984)

- Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Vladimir Fedoseyev (recorded at Moscow Radio Large Hall, Victor 1981; re-released Victor, CD 1995).

- Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal, conducted by Charles Dutoit (Decca, 1983).

- Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Sergiu Celibidache (EMI Classics, LP 1984, CD 2004).

- Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Lorin Maazel (Polydor, 1986).

- Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Alexander Rahbari (violin – Josef Suk) (Supraphon Records CD 11 0391-2, 1989).

- London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras (Telarc, 1990).

- Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Riccardo Muti (Angel Records, 1990).

- London Philharmonic, conducted by Andrew Litton (EMI, 1990).

- New York Philharmonic, conducted by Yuri Temirkanov, (violin – Glenn Dicterow) (RCA CD 1991).

- Orchestra of the Opéra Bastille, conducted by Myung-whun Chung (Deutsche Grammophon, 1993).

- Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Seiji Ozawa (PolyGram, 1994).

- London Philharmonic, conducted by Mariss Jansons (EMI, 1995).

- Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Robert Spano (Telarc, 2001).

- Kirov Orchestra, conducted by Valery Gergiev (Philips, 2002).

- Vienna Philharmonic, conducted by Valery Gergiev (Salzburg Festival, 2005). YouTube [2]

- Gimnazija Kranj Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Nejc Bečan (Ljubljana, 2010).[citation needed]

- Toronto Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Peter Oundjian (Chandos, 2014).

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Jacobson, Julius H.; Kevin Kline (2002). The classical music experience: discover the music of the world's greatest composers. New York: Sourcebooks. p. 181. ISBN978-1-57071-950-9.

- ^Minderovic, Zoran. 'Nikolay Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade, Symphonic Suite for Orchestra, op. 35'. Dayton Philharmonic. Retrieved 2008-10-25.[dead link]

- ^ abcdeRimsky-Korsakov, Nikolay Andreyevich (1942). My Musical Life. translated by Judah A. Joffe (3rd edition). Alfred A. Knopf.

- ^ abcdRimsky-Korsakov (1942:291–94).

- ^Abraham, Gerald, ed. (1990). The New Oxford History of Music, Volume IX, Romanticism (1830–1890). Oxford University Press. pp. 508, 560–62. ISBN0-19-316309-8.

- ^Lieberson, Goddard (1947). Goddard Lieberson (ed.). The Columbia Book of Musical Masterworks. New York: Allen, Towne & Heath. p. 377.

- ^ abMason, Daniel Gregory (1918). The Appreciation of Music, Vol. III: Short Studies of Great Masterpieces. New York: H.W. Gray Co. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ abc'Scheherazade, Op. 35'. The Kennedy Center. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^Taruskin, Richard (1996). Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the Works Through Mavra. Oxford University Press. p. 740. ISBN0-19-816250-2.

- ^Phillips, Rick (2004). The essential classical recordings: 101 CDs. Random House, Inc. p. 150. ISBN0-7710-7001-2.

- ^ abcdefgGriffiths, Steven. (1989) A Critical Study of the Music of Rimsky-Korsakov, 1844–1890. New York: Garland, 1989.

- ^Powers, Daniel (2004). 'Scheherazade, op. 35, (1888)'. China in Focus, Tianshu Wang, piano. Terre Haute Symphony Orchestra. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^ abSchiavo, Paul. 'Program Notes'. Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2007-07-06.

- ^Programme, Thirty-Eighth Season, Boston: Boston Symphony Orchestra, 1918–1919, p. 829, retrieved 2008-10-30

- ^Song of Scheherazade.

- ^Hare, William (2004). L.A. noir: nine dark visions of the City of Angels. McFarland. pp. 28–29. ISBN0-7864-1801-X.

- ^'U.S. figure skater Evan Lysacek wins gold medal'. Baltimore Sun.

- ^Jenkins, Sally (February 18, 2014). 'Meryl Davis and Charlie White's gasp-inducing performance in winning ice dancing gold'. The Washington Post.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rimsky-Korsakov - Scheherazade. |

- Scheherazade: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Scheherazade, 1001 Nights Retold in a Symphony – (NPR audio).

- Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade (Beecham-EMI) at the Internet Archive

Russian Easter Overture Mp3

Of all the great Russian nationalist composers of the latter part of the 19th century, Nikolai Andreievich Rimsky-Korsakoff (March 18, 1844 - June 21, 1908) stands second only to Mili Balakirev in his practical influence on the music created and preserved in that period. In so far as his own music is concerned, while some pieces have remained immensely popular, the bulk of his achievement is rarely heard today. Many people see him as the logical link between Modest Mussorgsky and Igor Stravinsky.

Rimsky-Korsakoff was the second son of a substantial landowner who lived 'in his own house' (as Rimsky-Korsakoff notes in his autobiography) on the outskirts of a small town, Tikhvin. Both his parents were musical and were quick to perceive that their son was unusually gifted; he had perfect pitch and excellent time and by the age of six he was having music lessons, but was not sufficiently enamored of music for it to supersede his love of books. In 1856 he was sent to the Naval College in St. Petersburg where he spent the next four years. He also began to go to the opera in St. Petersburg; struck first by Gaetano Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor and Robert le Diable, he later discovered the joys of harmony through playing manuscripts of Mikhail Glinka's Ruslan and Lyudmila and began making his own piano arrangements of excerpts from a range of favorite operas.

By 1861 the 17-year-old was becoming increasingly engrossed in musical studies and exploring the concert repertoire as well as opera. This same year he was introduced by his tutor to Balakirev, then aged 24 and already the leader of a group of young composers, including César Cui, Mussorgsky and Alexander Borodin. It was Balakirev who awoke in Rimsky-Korsakoff the ambition to become a composer, approving of his tentative sketches for a symphony and demanding that he complete it; even Nicolai's posting abroad (1862-65) did not dampen his ardor; he took the unfinished manuscript with him on his tour of duty. On his return to St. Petersburg he completed his symphony in time for its successful premiere under Balakirev's baton in 1865. Subsequent performances in 1866 confirmed his burgeoning reputation.

At this point he both idolized the domineering and opinionated Balakirev and was good friends with the younger and less musically trained Mussorgsky and Borodin. Still living what he termed the 'life of a dilettante', Rimsky-Korsakoff was looked upon as a talented but unfocused musical amateur by his composer friends, but as a brilliant musical talent by his colleagues in the navy. He himself was only too aware of his own shortcomings, and his orchestral works at this time tended to be quite short – the Overture on Russian Themes (1866) was given a successful performance in the same year, while 1867's Sadko, taken over from Mussorgsky who had abandoned an earlier attempt to set the subject to music, was a short and brilliant exposition of memorable melodies, showing real flair in the orchestration – a talent for which he would later become world famous. His Second Symphony, subtitled Antar, was completed in 1868.

At this time he began to realize his dreams of returning to his first musical love – opera. While on holiday with Borodin on his country estate, he resumed work on Pskovitianka (The Maid of Pskov). As he recalled: 'The picture of the impending trip to the dreary interior of Russia instantly brought an access of indefinable love for Russian folk life, for her past in general and for Pskovitianka in particular'. The opera engaged his attention intermittently for the next three years, while he also embarked on his second musical career – arranging and orchestrating the works of other composers. The recently deceased Darghomizsky had entrusted the completion of his almost finished opera The Stone Guest to Cui and Rimsky-Korsakoff; Nicolai did the orchestration, thus beginning a career as a collaborator in the works of his deceased colleagues.

In 1871, in an extraordinary development, the 'amateur' Rimsky-Korsakoff was offered the position of Professor of Composition and Instrumentation as well as leader of the St. Petersburg Conservatoire orchestra. After consulting Balakirev, the composer made his decision. As he comments in his reminiscences: 'Had I ever studied at all, had I possessed a fraction more knowledge than I actually did, it would have been obvious to me that I could not and should not accept…that it was foolish and dishonest of me to become a professor. But I, the author of Sadko…was a dilettante and knew nothing'. He took the job. With it came the awful realization of the depths of his ignorance, and for a while his creativity evaporated while he tried to develop what he felt to be a mature style. At this point in his life he felt secure enough to resign his naval commission, but was persuaded by Grand Duke Constantine to become instead inspector of naval bands.

The following year; Rimsky-Korsakoff, now 27, married Nadezhda Purgold; Mussorgsky was best man. In the same year he wrote his Third Symphony, a strangely formal affair which, in its original incarnation, was too concerned with the counterpoint, correct modulations and other formal matters which Rimsky-Korsakoff was desperately attempting to master for his professional peace of mind. As he consolidated his home and professional life, he found himself moving away from old colleagues: Balakirev, once a staunch atheist, had embraced religious mysticism and withdrawn almost entirely from his old circle of friends; Mussorgsky, in the first flush of success with Boris Godunov, had begun his slow physical and mental decline, brought on by alcohol.

In 1875, the year his daughter Sonia was born and his wife suffered a long illness, he began the editing and correction of Glinka's extant manuscripts, of which no definitive edition had been attempted since his death. By this time Rimsky-Korsakoff, now fully at ease with his own musical knowledge and techniques, had renewed his mission to bring more nationalistic traits into his music. These are very noticeable in the two operas which appeared next, May Night (1878) and The Snow Maiden, both of which dealt with specifically Russian themes and used old modes, folk-like melodies and nationalistic rhythms and scoring. The death of Mussorgsky in 1881 found Rimsky-Korsakoff once more realizing another composer's scores, spending nearly two years deleting, rescoring and editing the musical fragments and completed works he found among Mussorgsky's effects. This work, today somewhat controversial due to the extent to which Rimsky-Korsakoff departed from what Mussorgsky had composed, undoubtedly brought the composer's works into sharp focus in the public eye in the decades following his death. Without Rimsky-Korsakoff's reworking at Boris for example, the opera would not have achieved its status as a national treasure by the turn of the century. Equally, it was Rimsky-Korsakoff who made the first orchestral version of the piano work Pictures at an Exhibition, bringing it to the attention at concert-goers world-wide.

In 1883 the new Tzar, Alexander III, dismissed the old chapel musicians and appointed Balakirev as the new superintendent of the Court Chapel and Rimsky-Korsakoff as his aide. This led both of them into utterly unfamiliar territory, preparing choral music for the coronation and other important occasions. A favorite new prodigy, Alexander ('Sasha') Glazunov, was the young composer-acolyte who came to Rimsky-Korsakoff's aid in 1886 when the sudden death of Borodin left him with yet another disorganized heap of priceless unfinished compositions to put in order. Their major achievements were the performing version of Prince Igor and the realization of Borodin's unfinished Third Symphony, one movement of which Glazunov wrote down apparently from memory, having once heard Borodin play it on the piano.

Clearly all this work on other people's music slowed Rimsky-Korsakoff's own output considerably, and only by taking a break from his careful orchestration of Prince lgor during a summer holiday did he complete his sketches for Capriccio Espagñole, one of his most sparkling and delightful concert pieces. It is perhaps worth speculating whether the sublime melodies and scoring of the manuscripts he labored on for so long had a subliminal effect on the 'editor' who was also a great composer, releasing a flood of ethnically-inspired music which, in the following year, would include his single most famous piece, the suite Schéhérazade (musically illustrating characters and stories from the Arabian Nights) and the buoyant Russian Easter Overture.

This peak in his middle years was achieved – as he himself commented – 'without Wagner's influence'. But Wagner's influence was brought to bear when Rimsky-Korsakoff became involved in the production of Der Ring des Nibelungen in St. Petersburg. The Ring made little impact on the audiences at the time, but Rimsky-Korsakoff was impressed by the size and shape of the Wagnerian orchestra and used this in his next opera, Mlada, although he also incorporated the more exotic musical and dramatic devices he had witnessed in the Hungarian and Algerian cafés in Paris during the Universal Exhibition of that summer.

In the year after their return to St. Petersburg his family was struck by illness: first his mother died, then his wife and three of his children fell seriously ill, one of them dying while a second, Masha, remained critical. In summer 1892, the composer suffered what seems to have been a nervous breakdown, and was forced to take a prolonged break from music. In 1893 he had to deal with further illness, his son taking months to recover from a dangerous infection, while Masha continued to ail from consumption, dying that summer in Yalta.

Nikolai Rimsky Korsakov Russian Easter Festival Overture

Rimsky-Korsakoff had retired, but in the spring of 1894 his musical muse returned, and he began working on Christmas Eve, the first of a series of operas which would monopolize his creative interest until his death. This first manifestation was successfully premiered in 1895. With Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky and Borodin all dead, Rimsky-Korsakoff was unchallenged as the leading living Russian composer, and used his position both to promote his own operas and to forward the career of those composers in whose talents he firmly believed, such as Glazunov. Buoyed by the relative ease of his composition of Christmas Eve, Rimsky-Korsakoff next plunged into the legend of Sadko, completing an opera on it in 1896. It is in many ways his most accomplished opera and was very popular during his lifetime. After this, there was seldom a period when he was not devising, or working upon, his next opera, with The Tsar's Bride and Mozart and Salieri both completed before the end of the decade. With the opening of the new century The Tale of Tsar Saltan was produced privately in St. Petersburg.

Russian Easter Overture Rimsky Korsakov

In the next decade operas such as Pan Voyevoda (1903), Kastchei. The Immortal (1902), the dramatic prologue Vera Sheloga (starring the great bass Chaliapin), the mystical and extraordinary opera The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh (1905), and The Golden Cockerel all appeared. During these years Rimsky-Korsakoff kept a high public profile, culminating in open discord with the St. Petersburg Conservatory when students in 1905 rebelled against what they saw as an oppressive and conservative musical autocracy. The forthright Rimsky-Korsakoff could not help but publicly agree with the students. As a result, his own works were banned from performance in St. Petersburg and the school's classes were suspended indefinitely; instead Rimsky-Korsakoff's students studied with him at his house. He was to remain at the hub of St. Petersburg and Moscow musical affairs until his death three years later from a progressive throat and lung disease.